|

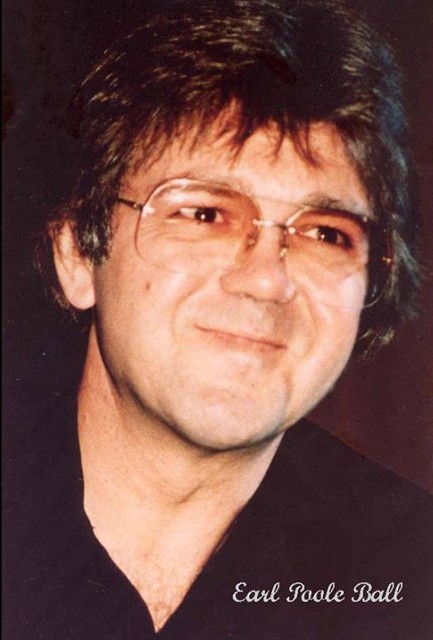

"My earliest childhood musical memory is sitting with my maternal grandmother Julia Stringer Morris on Saturday nights by her radio and listening to the "GRAND OLE' OPRY." This inspired my love of country music and live performance." EPB

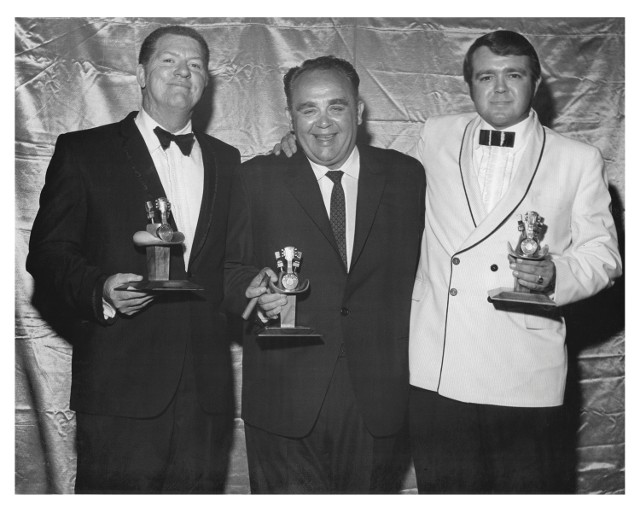

ACADEMY of COUNTRY and WESTERN MUSIC AWARDS, LOS ANGELES, 1968

(L-R) RED WOOTEN - Bass Award, CLIFFIE STONE (My Mentor) Publisher Award, EARL POOLE BALL Piano Award!

"Cliffie Stone is responsible for much of my success in life. He gave me a chance to leave the bars and work hard at being a Music Man!! I am forever grateful for his trust and guidance." EPB

|

Ask Earl Poole Ball to describe himself and he’ll answer simply; “I’m a rockabilly piano player and singer” Well yes, and Chuck Berry played a little guitar!

By rights, Ball should be in just about every Americana Music Hall of Fame there is --- and several they haven’t dreamed up yet. In addition to being Johnny Cash’s longtime piano player, the man dubbed “Mr. Honky-Tonk Piano” backed everyone from the Byrds to the Buckaroos. As a producer, songwriter, and arranger, he’s left an indelible mark on the Billboard country charts, along the way playing an important role in the evolution of alt-country. His old business card lists three names under his own: Gram Parsons, Johnny Cash, and Wynn Stewart. “All of my references are dead,” he notes with a wistful smile.

Earl Ball, on the other hand, is still rolling. It’s a long, circuitous road from Ball’s tiny hometown of Foxworth, Mississippi, to his current residence in Austin. “When I was about 8, my mother told me I should take piano lessons,” he remembers. “Around 14, I decided I wanted to play popular music, and got to where I could figure out those country songs I’d been listening to on the radio --- Web Pierce and Faron Young. Back then country was called “hillbilly music.” I met some guys who were putting together a hillbilly band called the Hillcats. We played the VFW hall where they had a piano. I’d take the lid off so it could be loud.”

At 16, the aspiring young showman hitch-hiked to nearby Hattiesburg, where local DJ Jimmy Swan was hosting a weekly television show, Red McCaffrey’s Supermarket Showtime. “It was on 30 minutes – one camera, live,” Ball says. “I auditioned on piano and got the job. Every Thursday night, after school, I’d hitch-hike the 33 miles to the grocery store to do the show.”

The experience gained Ball valuable performing chops, and he became adept at projecting confidence in front of a camera.

Former Louisiana governor and occasional singer Jimmie Davis “You Are My Sunshine” caught Ball on TV and, impressed, invited him to play on his next record. It was Balls’ first professional experience in a recording studio and he was hired as the opening act at stump appearances for Davis’ 1959 comeback election campaign. Along the trail, he met up with a fellow piano player named Malcolm Rebennack, who taught him the blues scale on keys. The helpful tutor would later achieve fame as Dr. John.

By 20, Ball was itching to travel and expand his horizons. “I really wanted to get out of Mississippi,” he recalls. “It was hard to be a kid with liberal thinking there.” Packing his piano and heading for Texas, Ball spent the next three years pumping out songs at the Silver Dollar Lounge in Houston, while selling washing machines during the day at a department store. He lit out for California in 1963, eventually landing a regular gig with friend Vern Stovall outside Los Angeles at a nightclub called The Aces.

After hours, Ball began hosting nightly jam sessions, which quickly became a local sensation, attracting top-tier musicians and industry big-wigs. “I knew how to get good players together….get jazzers together, country guys together. It was kinda like an emcee job.” He started getting calls for regular session work from such high-profile West Coast-based country acts as Buck Owens and Merle Haggard, acquiring a reputation as a versatile and talented sideman.

One night a young fringe-topped buckaroo-wannabe named Gram Parsons dropped in, looking for a piano player and the two musicians hit it off. The pompadour-topped Ball and the dandy-ish Parsons made for an incongruous-looking due, but the magic was palpable. “Gram was a really good, cool, straight-ahead guy,” remembered Ball. “Liked to smoke a little grass, but he seemed to be really together, knew what he wanted.”

What Parsons wanted was to synthesize traditional country with rock ‘n roll, and in Earl Ball, he found a kindred spirit and mentor. “Gram loved country. He wasn’t the greatest singer in the world, but he sang with more heart than almost anybody I knew,” Ball says. “I was already playing with his heroes. I’d go over to his house, we’d talk about music. It was like, “OK, get a little high, I’ll drink a little whiskey, and let’s play some music”.

Along with bassist Chris Ethridge, Parsons was in the process of forming the International submarine Band – later the Flying Burrito Brothers – asked Ball to play on his new album, Safe At Home.

In his final interview before his death last April, Ethridge spoke with Texas Music about Ball: “I remember when I first met Earl,” Ethridge recalled. “I was wondering how somebody with such big ol’ fingers could play like that. He could play anything that was called for --- rock ‘n’ roll, blues, honky-tonk.” Safe At Home would come to be regarded as a seminal touchstone in the birth of alt-country. “I can’t believe how many people were influenced by that record,” marveled Ethridge some 45 years later.

By the time Safe At Home was in the can, Parsons had joined the Byrds, then in a midst of a stylistic makeover. Amid conflicts of ego within the group, Parsons recruited Ball to play on the band’s next album. “They were all smoking grass,” Ball says, recalling the acrimonious sessions. “I didn’t know if it was because they were stoned and didn’t know what they were doing, or if there was some element of non-acceptance of each other, but there was a strange vibe.” Despite the tensions, the result was one of the era’s most revered albums, 1968’s Sweetheart of the Rodeo. Ball’s solo on “You’re Still on My Mind” is a highlight, deftly mingling woozy honky-tonk with a rocker’s swagger.

By the late 60’s, the now-veteran sideman was working with such diverse crossover artists as aging teen idol Rick Nelson (“he was more interested in playing drums than singing”), troubled troubadour Phil Ochs (“a sincere but intense individual”) and ex-Monkee Michael Nesmith. Between sessions, the enterprising Ball began successfully hustling songs at Capitol Records for emerging talents Glen Campbell and Linda Ronstadt.

Recognizing a valuable resource, Capitol Records hired Ball as a contract producer, transferring him to Nashville in 1972. After the casual vibe of the West Coast, Ball found Music city to be a horse of a decidedly more traditional color. “The records were made differently,” he says. “It was real commercial, very regimented. But I was getting another introduction into the art of recording. They started giving me country acts to oversee. I produced Freddie Hart’s follow-up to Easy Loving. Everybody thought he’d fall on his ass after that --- and maybe I would too --- but then we scored three Number 1 singles.”

Juggling session work, producing duties, and touring kept Ball perpetually busy --- so busy he had to turn down an offer from legendary guitarist James Burton to join Elvis’ stage band. Ball may have continued his prodigious producing and songwriting career indefinitely, but in January 1977 he was offered a game-changing recording gig with Johnny Cash. “Whoever Johnny was using on piano was out of town, so they called me to play on the session,” Ball recalls. “After the second song, he had his guitar player ask me if I wanted to go on the road as his piano player.”

Ball became Cash’s piano player of choice on tour and in the studio, also producing one of Cash’s most acclaimed albums, Rockabilly Blues, a return to the singer’s Sun-era roots. “Johnny was up and down, in and out of his sobriety during all of that,” Ball says. “He was clean by then, but he did drink a little wine when he’d record. It was kind of like a religious thing with him, because Jesus made wine and all that.”

Ball settled into the next 20 years as Cash’s go-to-piano player, with occasional breaks to pursue a sideline career as an actor in such films as: Texasville and The Thing Called Love. Finally, in November 1997, he received word that because of declining health issues, Johnny and June Carter Cash were retiring from the road. Ball had seen it coming: “He started forgetting lyrics at shows, playing erratically. He had to have yellow tape laid out on stage so he’d know where to walk. We knew we were in trouble.” When he died in 2003, Cash left Ball his distinctive white baby grand as a keepsake, which still graces Ball’s living room.

In the wake of Cash’s death, Ball found himself at a crossroad. After a brief but surreal residence in Branson, Missouri, he was contemplating his next move when an old friend suggested moving back to Texas. “I knew Dale Watson from California,” Ball says. “We’d talk constantly about my coming to Austin. He told me I could stay with him.” Ball took Watson up on his offer, finding Austin’s casual ambience and impressive roster of master musicians compatible with his own laid-back sensibilities. “Dale set me up so I got known around town, getting me bookings when he was out touring” Ball says. “I got here June 19, 1999 and I’ve been here ever since.”

Watson says he knew Austin would embrace Ball --- and vice versa. “I met Earl in Los Angeles in the mid ‘80’s,” Watson says. “He was already a big deal there, and every chance to play with him was a joy. It seemed Austin and Earl was a natural fit. I used him on every record I could and every gig I could until his own shows started to take off.” Ball quickly became a local favorite, equally embraced among both traditional country lovers and the rowdier rockabilly crowd.

Fifteen years later, despite a tricky back and grueling schedule, Ball shows no signs of slowing down; playing rotating gigs in more bands than he can count (Earl Poole Ball and the Cosmic Americans, the Lucky Tomblin Band, Heybale, and Rockabilly Bluze Band). At 72, he appreciates both where he’s come from and where he’s landed.

“I like the fact that I can play what I want, do it well, and find acceptance in it,” he says. Then, glancing up from his dog-eared appointment book, “Mr. Honky-Tonk Piano” smiles wryly, “I had six gigs last week and seven the week before. It seems I’m too popular for my own good.”

By Steve Uhler, Texas Music

|